Eliminating Imaginary Frequencies

by Corin Wagen · Dec 1, 2025

When running optimizations in computational chemistry, it's almost always necessary to run a frequency calculation afterwards to check that the optimization found a true minimum. Calculating vibrational frequencies entails computing the nuclear second derivatives of the energy (the Hessian matrix), removing the rotational and translational components of this motion, and then determining the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the resultant matrix. If all frequencies are positive, the geometry is a true minimum.

If one more frequencies are imaginary (often representented as negative in computational outputs), then something's gone wrong: either the optimization is not fully converged or it's converged to a saddle point. Optimizations can fail to converge due to noisy gradients (common with older neural network potentials or some implicit-solvent models) or loose convergence parameters; resubmitting with tighter convergence parameters can often address this problem. Spurious saddle points can typically be avoided by perturbing the structure slightly and resubmitting the structure.

Checking calculations in this way is an important step in careful reactivity modeling. We try to make this easy through Rowan; when both optimization and frequency calculations are requested, Rowan automatically checks that there aren't any imaginary frequencies and alerts the user if there are. Typically, small imaginary frequencies can be removed simply by reoptimizing with tigher constraints or by resubmitting a slightly perturbed structure, but occasionally removing imaginary frequencies can be quite difficult.

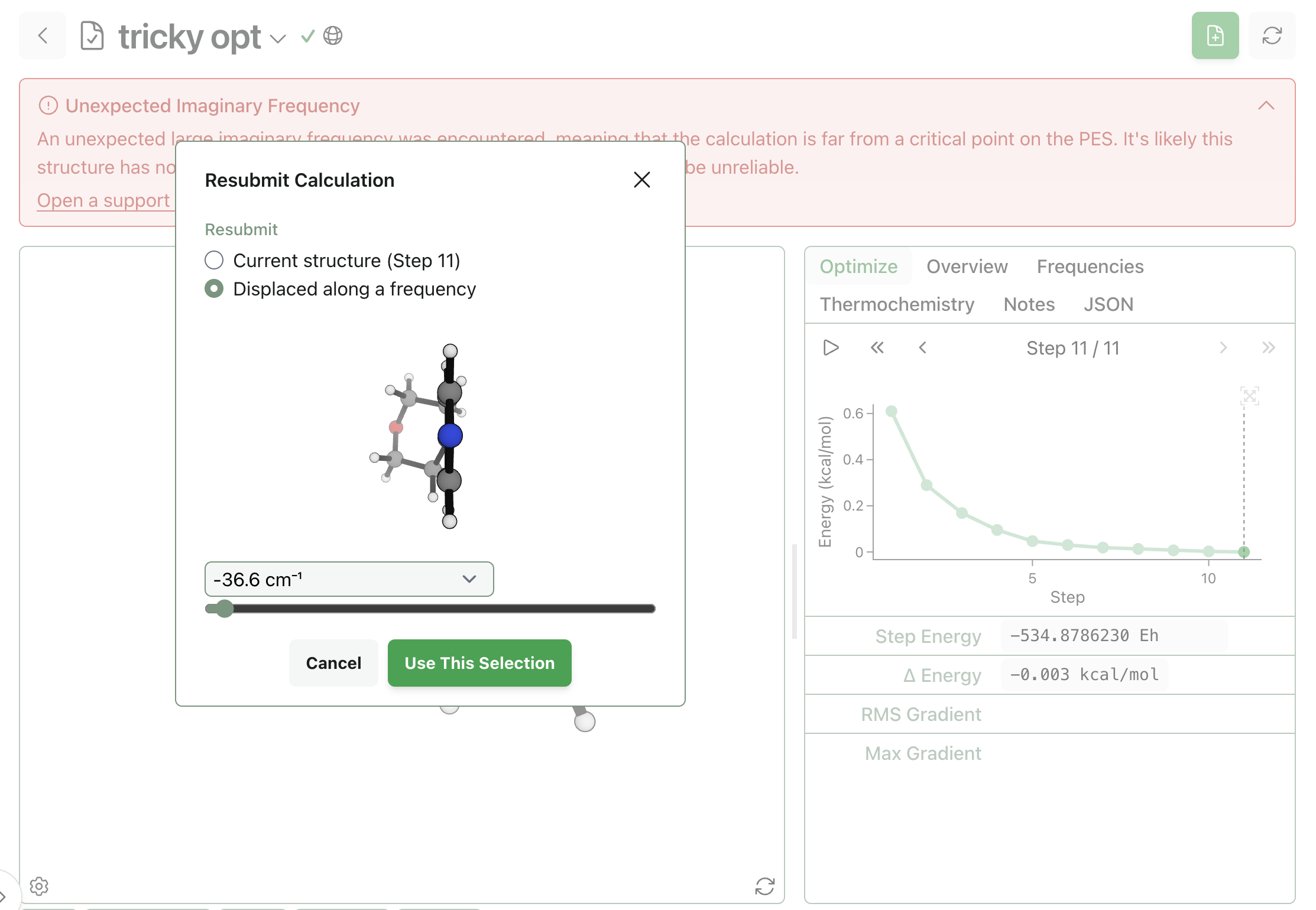

Last week, a customer reached out with a tricky issue; they were trying to run multi-stage optimizations on a certain structure, but were unable to remove an imaginary frequency even after repeated resubmission. I was able to help the user solve their problem and—with their permission—am sharing a truncated version of the structure and showing how we ultimately solved the problem.

Here's the molecule in question, 4-morpholinopyridine. Drawing the pseudoaxial conformation of this structure and optimizing it with eSEN-OMol25-sm-conserving (Rowan's default NNP) leads to a 37i cm-1 imaginary frequency:

Solution #1: Torsional Scan

Inspecting the imaginary frequency in question allows us to visualize what motion is associated with the saddle point. Upon careful inspection, it seems like the imaginary frequency is rotating the pyridyl group with respect to the morpholine ring, suggesting that perhaps the ring torsion is not fully relaxed.

To investigate this further, I used Rowan's scan workflow to see how the energy changed as the morpholine–pyridine torsional angle was varied. The initial optimization had a C13–C7–N6–C5 angle of 17.7º, corresponding approximately to step 19 on the scan. After running the scan, we can see that the minimum is actually at around 8º (step 9), about 0.05 kcal/mol below the starting structure.

Resubmitting from the 8º scan structure produces a structure with no imaginary frequencies, meaning that it is a true minimum on the potential energy surface.

Solution #2: Resubmitting a Perturbed Structure

The above solution requres two separate workflows and a bit of chemical intuition. To help make removing imaginary frequencies even more painless, Rowan contains a special resubmission mode that makes it easy to resubmit structures perturbed along the imaginary vibrational mode.

From the failed optimization, I selected "Resubmit" and then chose to resubmit from a structure "displaced along a frequency." I selected the imaginary frequency in question and then dragged the slider all the way to the left to rotate the torsional angle away from the metastable state.

Resubmitting this structure to the same optimization and frequency sequence as before led to a structure without any imaginary frequencies:

Stepping back for a second—why did this optimization require special treatment? The original structure with the 36.6i cm−1 imaginary frequency had a plane of symmetry; the morpholine group was exactly centered with respect to the pyridine ring. User input helps to break symmetry and avoid the metastable saddle point, pushing the structure down to one of two equivalent conformers. This isn't an infrequent problem with high-symmetry systems, and manually removing symmetry is necessary in many such cases.