Rowan Research Spotlight: An Kitamura and Jake Evans

by Corin Wagen · Mar 4, 2025

What if we could power entire cities with giant tanks of stable organic molecules? And what if, with a flick of a switch, those same molecules could capture and release carbon dioxide? These are just a few of the questions driving the research of An Kitamura (a fourth-year graduate student) and Jake Evans (a postdoctoral researcher) in the Malapit lab at Northwestern. In a recent conversation with Corin Wagen from Rowan, An and Jake shared how they're tackling some of chemistry's toughest challenges, and how Rowan's computational tools have helped them in this undertaking.

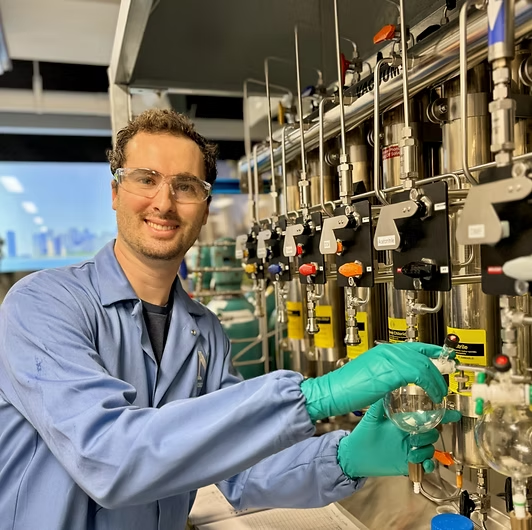

An Kitamura

From Small Electronics to Grid-Scale Storage

The Malapit group's work on organic redox-flow batteries aims to solve a critical energy problem: how to store large amounts of renewable electricity efficiently and affordably. Lithium-ion batteries power laptops, phones, and cars, but upscaling lithium for entire power grids quickly becomes expensive and impractical. Redox-flow batteries, by contrast, store their electroactive materials in external tanks rather than sealed compartments. To scale the capacity of system, you simply expand the tanks—an ideal scenario for grid-scale applications.

But redox-flow batteries have their own complications. For years, most redox-flow batteries have relied on metal ions like vanadium (like this massive redox-flow battery built by Rongke Power). They work well but can be costly, and their water-based operation limits the maximum voltage because the electrochemical solvent window for water is relatively narrow. Non-aqueous solvents like acetonitrile or DMF have much wider solvent voltage windows, making them an appealing alternative.

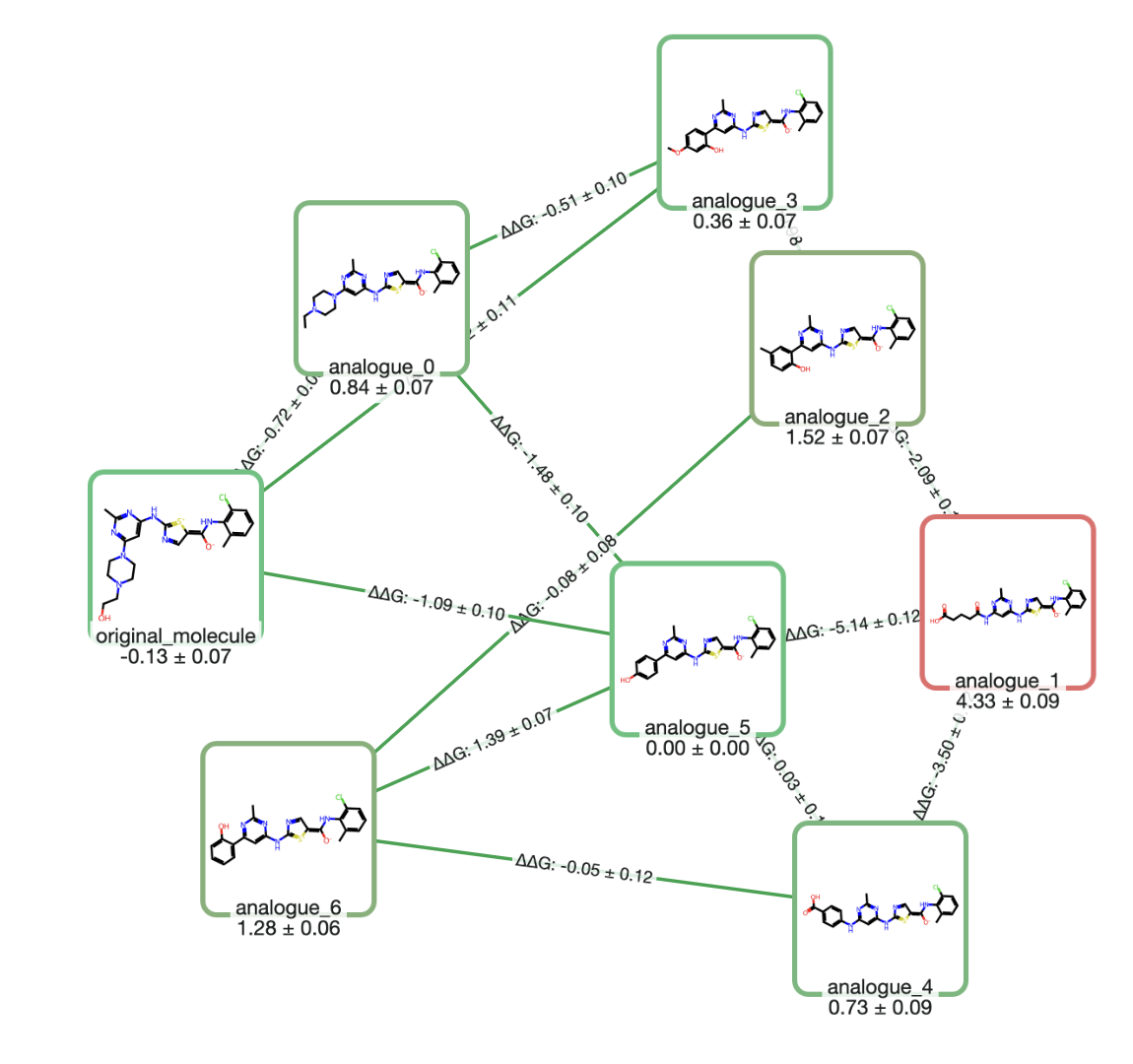

Switching to organic solvents and electrolytes comes with different stability challenges, though. Organic radicals are often highly reactive and can undergo all sorts of unwanted processes, like polymerization and degradation, and overcoming these instabilities is the heart of An's research. She looks through the literature for electroactive organic molecules that might have favorable properties, and design analogs with improved stability and charge/discharge voltages.

Electrochemical Carbon Capture

Flow batteries aren't the lab's only area of interest. Jake Evans has been exploring how to leverage the team's stable organic redox molecules for reversible CO2 capture. Most industrial carbon-capture technologies rely on heat to release CO2—an expensive, energy-intensive process. The Malapit lab's approach, by contrast, uses electrochemistry as an on/off switch.

Jake Evans

Jake's work focuses on using ketones to capture carbon dioxide. While ketones and CO2 "just stare at each other," Jake says, reducing the ketone to generate a negatively charged oxygen generates a species that can attack CO2. Quinones have been used in similar ways, but An discovered a class of ketone-containing molecules that appear more stable than standard quinones. This platform lets Jake pump in electrons to capture carbon dioxide, then reverse the current to release it. This approach also has the potential to scale more than existing methods—"with a flow system you can just increase the size of the tank to capture arbitrary amounts of CO2," Jake explains.

While the concept sounds straightforward, the team must carefully study the redox potentials and binding equilibria of each molecule to predict whether a newly designed ketone will bind enough CO2 under real-world conditions—like flue gas or even ambient air. The net result could be a more energy-efficient way to shuttle CO2 in and out of solution, opening new avenues for carbon capture and utilization.

How Rowan Helps

An and Jake credit Rowan's user-friendly computational platform for giving them useful insights throughout the course of their research. The ability to predict redox potentials with Rowan has been "huge" for the electrosynthesis projects, says Jake. "Rowan has helped us mitigate unwanted reactions that cause issues such as grafting and over-oxidation." Computation "was actually a major move forward in this project and helped us understand what was going on… I had no idea how to do computational chemistry and Rowan made it so easy to just try."

Calculations have also been useful in the redox-flow-battery project. Redox potential predictions help them to understand which compounds are likely to be within the desired voltage window, while studying redox-based changes in geometry helps them to understand trends in stability. "There's some degradation pathways that we haven't fully figured out yet," Jake explains, and Rowan's pKa prediction and Fukui index workflows can help to understand which sites might be reactive. At one point, they thought that degradation was occurring at a specific carbon atom, only for calculations to point them towards an oxygen atom instead—which proved to be right.

An and Jake's story demonstrates that the right computational tools can accelerate practical innovation in the lab, helping researchers work more efficiently and design better experiments. As their projects move closer to publication, they look forward to sharing more details with the scientific community—stay tuned!

If you're interested in following along with this research, you can follow the Malapit Lab and Professor Christian Malapit on X (Twitter).

And if you're interested in being the subject of a research spotlight like this, fill out our interest form and we'll get back to you!