Modeling Addition and Substitution Reactions

by Milca Pierre and Ari Wagen · Mar 20, 2025

This blog was written with friend of Rowan Milca Pierre. Milca is an undergraduate studying chemistry at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

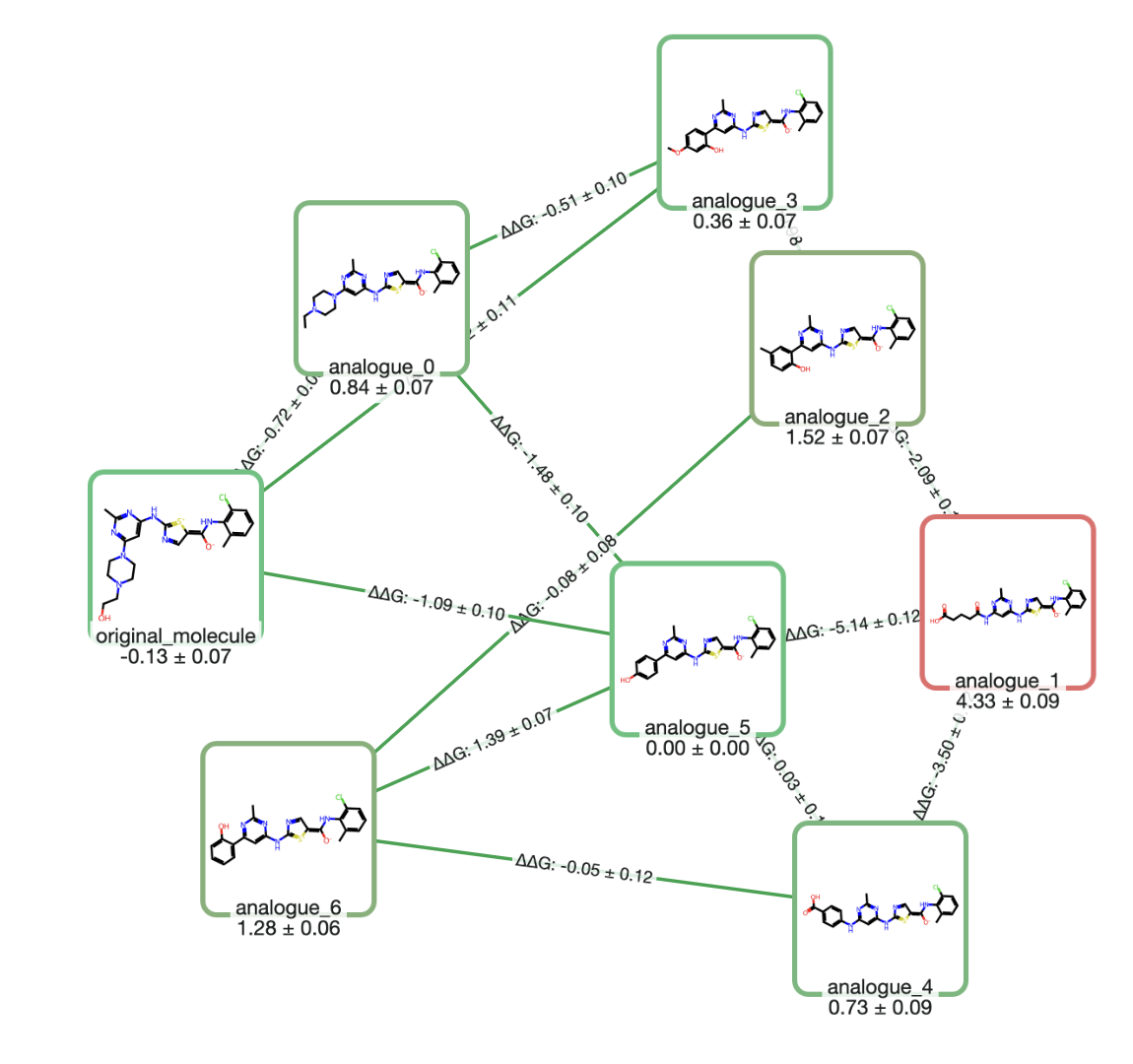

In this blog post, we'll be looking at an exercise from The Molecular Modeling Workbook for Organic Chemistry by Warren J. Hehre, Alan J. Shusterman, and Janet E. Nelson (Internet Archive, Amazon). Exercise 1 of chapter 13 looks at addition and substitution reactions, asking:

Unsaturated hydrocarbons undergo a variety of reactions. Experimentally, alkenes & alkynes undergo addition reactions whereas aromatic molecules, such as benzene, undergo substitution reactions instead. Why?

To answer this question, the workbook directs us to calculate the thermodynamics of each reaction. We'll be looking at two different sets of products (cyclohexane and benzene) and calculating the energy of the addition of bromine and corresponding substitution reaction for each.

Our goal is to determine which reactions are exothermic, which are endothermic, and by how much.

Figure 1: Addition and substitution reactions of cyclohexene and benzene with Br2

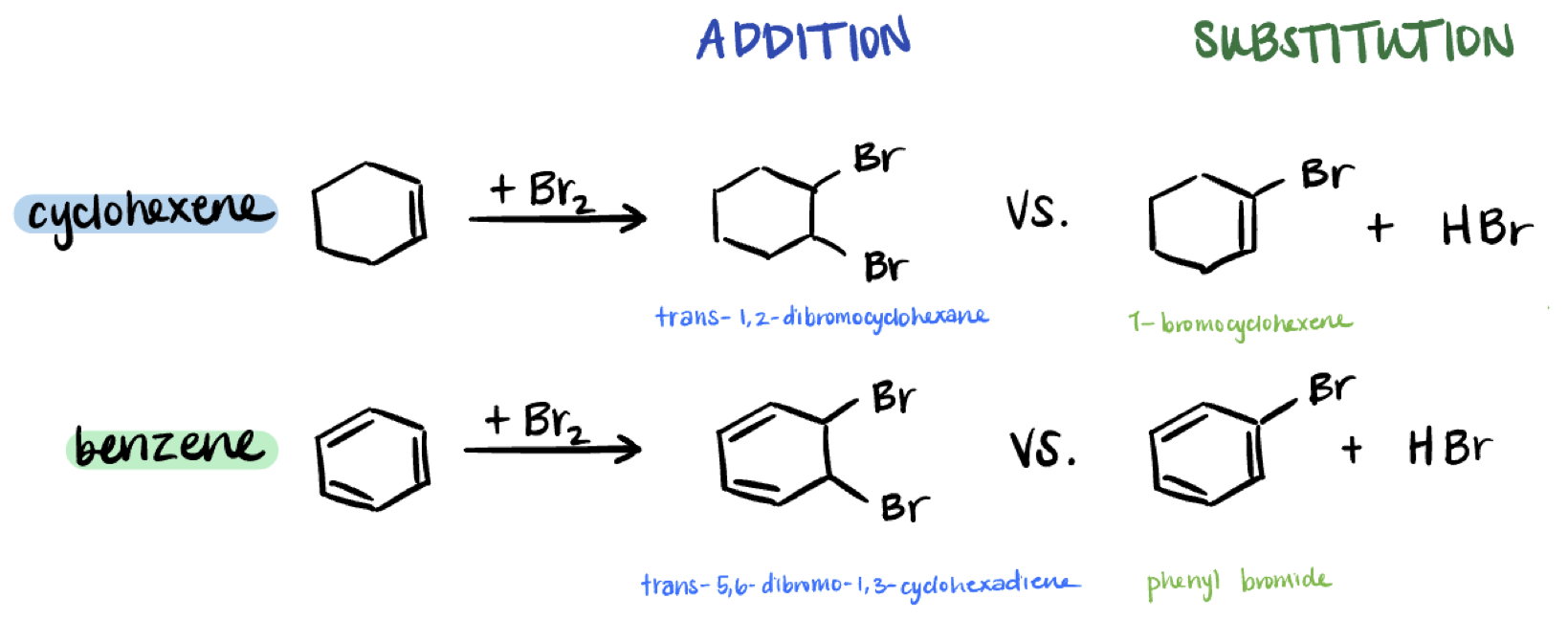

To quickly explore the thermodynamics of these reactions, we'll calculate the energy of each set of reactants and products using the AIMNet2 (ωB97M-D3) level of theory.

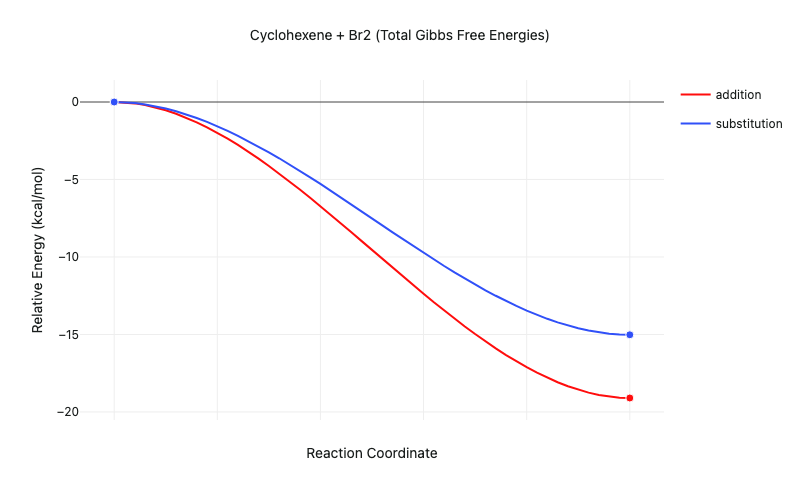

Cyclohexene + Br2

Here are the involved Rowan calculations:

- Addition: cyclohexene + Br2 → trans-1,2-dibromocyclohexane

- Substitution: cyclohexene + Br2 → 1-bromocyclohexene + HBr

Running these optimizations and plotting the thermodynamic change using Rowan's graph builder utility shows us that, although both the addition and substitution reactions are exothermic, the addition reaction is more exothermic. The addition reaction is, therefore, thermodynamically favored, accounting for the observation that "alkenes & alkynes undergo addition reactions."

Figure 2: Thermodynamics of the cyclohexene + Br2 addition and substitution reactions (transition states not modeled)

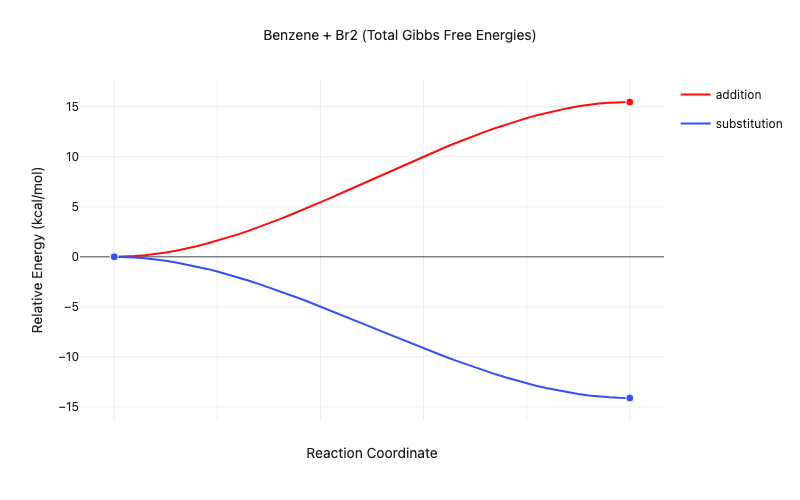

Benzene + Br2

Here are the involved Rowan calculations:

- Addition: benzene + Br2 → trans-5,6-dibromo-1,3-cyclohexadiene

- Substitution: benzene + Br2 → phenyl bromide + HBr

The results of these calculations show that the addition reaction is endothermic, while the substitution reaction is exothermic. This means that the substitution reaction is thermodynamically favored, explaining the observation that "aromatic molecules, such as benzene, undergo substitution reactions."

Figure 3: Thermodynamics of the benzene + Br2 addition and substitution reactions (transition states not modeled)

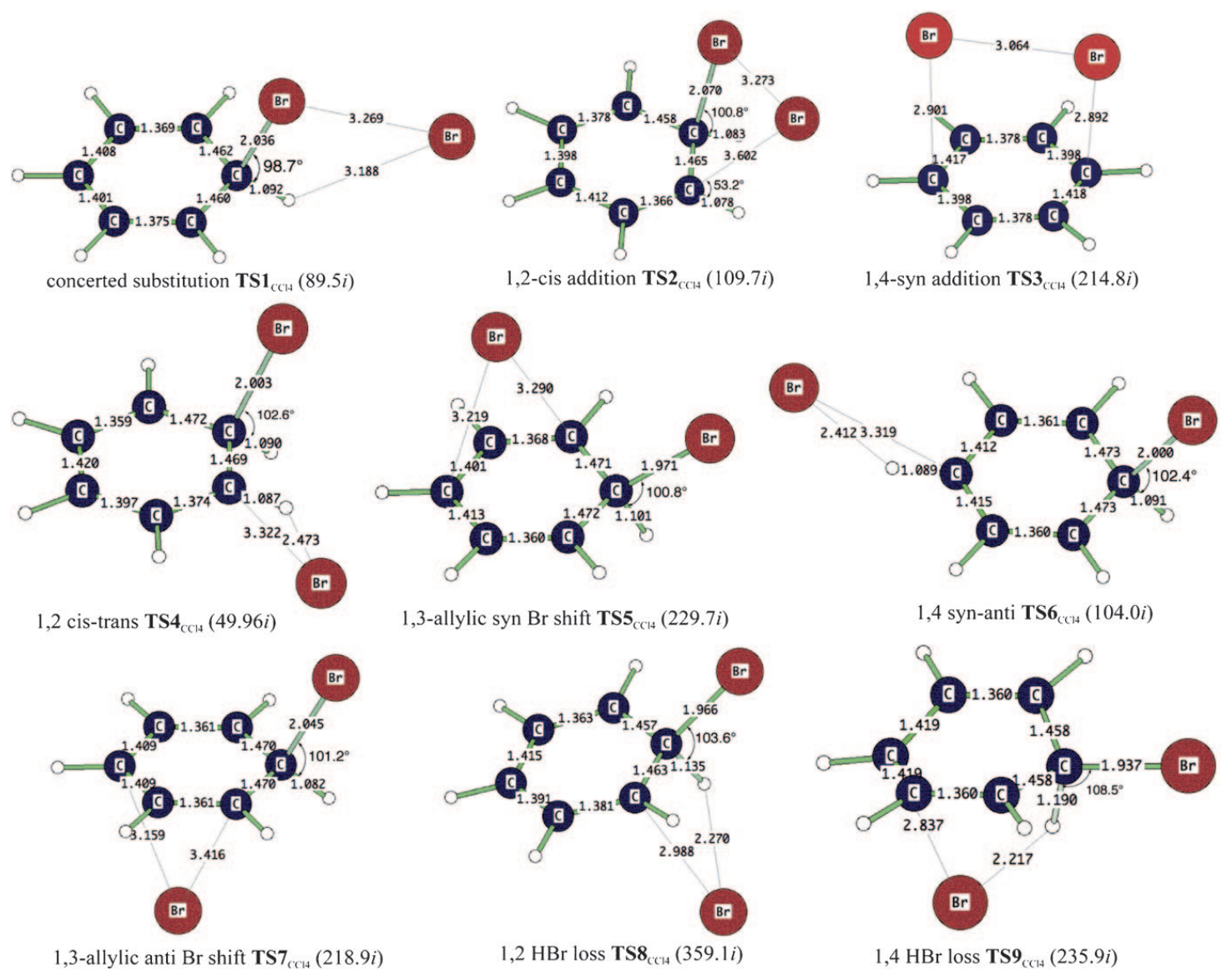

To model these reactions' kinetics and predict which pathways would be kinetically favored, we would need to find and optimize each involved transition state. This would be a research project too large for a single blog post—these reactions are very solvent-dependent, may directly involve multiple solvent molecules or catalysts, and the transition-state structures are hard to find. We encourage the interested reader to see other sources looking at these reactions, including:

- "16.1: Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions - Bromination" from Organic Chemistry (Morsch et al.)

- "The Inherent Competition between Addition and Substitution Reactions of Br2 with Benzene and Arenes" from Jing Kong and co-workers at the University of Georgia

Figure 4: Computed transition-state structures of the benzene + Br2 substitution and addition reactions. Reproduced from figure 2 in Kong et. al (2011).

If you're interested in using Rowan to model your own reactions, you can do so through Rowan's web platform (it's free to make an account and get started). Happy computing!